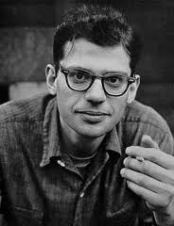

Oh, Allen …

Firstly, I should note that although I agree 110% (and yeah, stats fans, I know that is not actually physically possible) with everything my blogging partner-in-crime said in his post on Ginsberg’s Howl, I may have unwittingly succumbed to what I will call the Kazuo Ishiguro syndrome. “I won’t post my blog until the weekend,” I told Andy a few days ago, “because I want to watch the film Howl first.” Just like over a year ago when I told Andy, ”Oh, I’ll have my Ishiguro blog up after I’ve seen Never Let Me Go … “ And in both cases, watching the respective films tempered my original feelings about the respective books, subsequently resulting in much more lenient posts than perhaps would have been submitted otherwise.

Like Andy, when it comes to the Beats, I, too, read Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs at an early age – both in my very late teens – and loved them. Especially Kerouac, whose On The Road is one of my Favourite. Books. Of. All. Time (along with The Place of Dead Roads from the Burroughs canon). So that is why you will never see anything from either of these authors in ANRC (and quite frankly, if you haven’t read everything they’ve ever done by now, well … )

Like Andy, when it comes to the Beats, I, too, read Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs at an early age – both in my very late teens – and loved them. Especially Kerouac, whose On The Road is one of my Favourite. Books. Of. All. Time (along with The Place of Dead Roads from the Burroughs canon). So that is why you will never see anything from either of these authors in ANRC (and quite frankly, if you haven’t read everything they’ve ever done by now, well … )

I had this idea that Howl and Other Poems would be a reasonable-sized collection, but in fact it amounts to little more than 20 pages. Hence, although our main objective was Howl, we ended up plumping for Selected Poems 1947-1995 (and I bet you’re pleased, Andy, that we didn’t end up going for Collected Poems, huh?) I have to admit that I didn’t read every single poem amongst its 400-odd pages, but I certainly read enough – and skimmed enough more – to get an overall view of Ginsberg’s work.

I’ll try to be kind here. I think these poems have obviously and markedly dated – and not very well, at that. Or perhaps you need to be young and impressionable for them to really hit their mark. Ginsberg was 29 when he wrote Howl; he primarily considered himself a performance poet, and Howl was famously first unveiled to a reportedly enthusiastic audience at a San Francisco gallery in October 1955. I read Howl – all eight parts of it – aloud (take that, annoying neighbours!) because that is how I think poetry should be consumed to be truly appreciated. Otherwise it is too easy to skim over; plus it robs the reading of the aural testimonial to its rhythms and cadence. It is easy to understand how these words and themes would have been considered electrifying and incendiary in 1955 (indeed, Ginsberg’s publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti ended up in court on obscenity charges in 1957, but was acquitted, in a major coup for free speech and anti-censorship). Unfortunately, in 2012, I daresay Howl comes across as just another long-winded treatise on sex (both gay and straight), drugs and railing against the establishment. Ginsberg may have been a trailblazer back in the day, but for mine, these words simply no longer pack a punch.

(Aside: it probably doesn’t help that the whole time I was reading Howl, I had They Might Be Giants I Should Be Allowed To Think going around in my head. If you’re unfamiliar with TMBG – and they’re an awesome band – check it out here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s8wQKEC5kHkc)

Howl, Before and After: San Fransisco Bay Area (1966-56) – as presented in Selected Poems, curated by Ginsberg himself, a year before his death at the age of 70 – is dedicated to Kerouac, Burroughs and Neal Cassady, a writer-of-sorts (his roman a clef was posthumously published), all-round rabble-rouser and Ginsberg’s sometime lover. It opens with the short introduction Malest Cornifici Tuo Catullo (which Google translator tells me is Latin for “Badly Defeated, You’re Crazy”), an open letter to Kerouac; followed by Dream Record, June 8, 1955, a eulogy to Burroughs’ de facto wife Joan Vollmer, shot by her husband in a drunken game of William Tell several years earlier.

The three-part Howl, is, obviously its centrepiece, if not masterpiece; dedicated to the writer Carl Solomon, it retells the lives and myths of Ginsberg’s closest associates in an ambitious, unwieldly, stream-of-consciousness tract that misses as often as it hits. Overall, it’s impressive enough, especially within its timeframe and social context, but – to use a baseball analogy – I expected to be belted out of the ballpark, not meekly pushed to second base. It is followed by Footnote to Howl, a hallucinatory, celebratory ode to those same friends, surprisingly steeped in Christian-esque platitudes (obviously Ginsberg was yet to discover Buddhism at that point).

A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley is a short, throwaway rumination on life in a new abode. A Supermarket In California imagines a late-night encounter with Ginsberg’s idol Walt Whitman, while Sunflower Sutra details an stoned afternoon with Kerouac and Many Loves recounts, sometimes cringingly so, the poet’s first sexual encounter with Cassady.

But the piece that struck me the most is the second-to-last poem America, a riveting, prescient tirade against the motherland that plays out like a scene of separating lovers (“America I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing”), chock-full of anger, remorse and recriminations. Finally, here I could see what all the fuss is about – that amongst the meandering dross, Ginsberg was capable of overwhelmingly powerful poetry. But at the end of the day that’s only one out of Howl’s nine poems that absolutely, inexorably blew me away.

So, should you read Howl, or any Ginsberg for that matter? Well, for better or worse he’s still considered a crucial plank of the Beat Generation – so sure, knock yourself out if you’re a completist. Or you can just watch the film instead – with the added benefit that actor James Franco a.) Reads most of Howl aloud on-screen; and b.) Manages to bring a certain cinematic sexiness to Ginsberg, whom one would never accuse of being a spunk-rat in real life. Franco is quite good in Howl, but absolute shite when it comes to putting pen to paper under his own name. Trust me – I read his debut short-story collection Palo Alto last year, and that’s a couple of hours of my life I will never get back.